Stanford researchers have developed a flexible material that can change both its colour and texture in seconds, mimicking the camouflage abilities of octopuses and cuttlefish with a precision finer than a human hair.

The study, published in Nature, details a significant leap forward in synthetic materials. While scientists have long struggled to replicate the dual-action disguise of cephalopods — which can alter their skin’s 3D texture and pigmentation simultaneously — the new “photonic skin” can swell into complex 3D shapes and shift through a rainbow of colours on command.

“Textures are crucial to the way we experience objects, both in how they look and how they feel,” said Siddharth Doshi, a doctoral student at Stanford and lead author of the paper. “These animals can physically change their bodies at close to the micron scale, and now we can dynamically control the topography of a material — and the visual properties linked to it — at this same scale.”

A happy accident

The breakthrough relies on a technique called electron-beam lithography, usually reserved for semiconductor manufacturing. By firing a beam of electrons at a polymer film, researchers discovered they could control how much specific areas would swell when exposed to moisture.

This mechanism was found by accident. Doshi had been using a scanning electron microscope to image nanostructures on a polymer film for a previous project. Instead of discarding the sample, he reused it, only to notice that the areas touched by the electron beam behaved differently, changing colour and texture when wet.

“We realised that we could use these electron beams to control topography at very fine scales,” Doshi said. “It was definitely serendipitous.”

The precision of the technique is such that the team created a nanoscale, rising replica of Yosemite National Park’s El Capitan. Perfectly flat when dry, the monolith’s famous geometry rises from the surface the moment water is added.

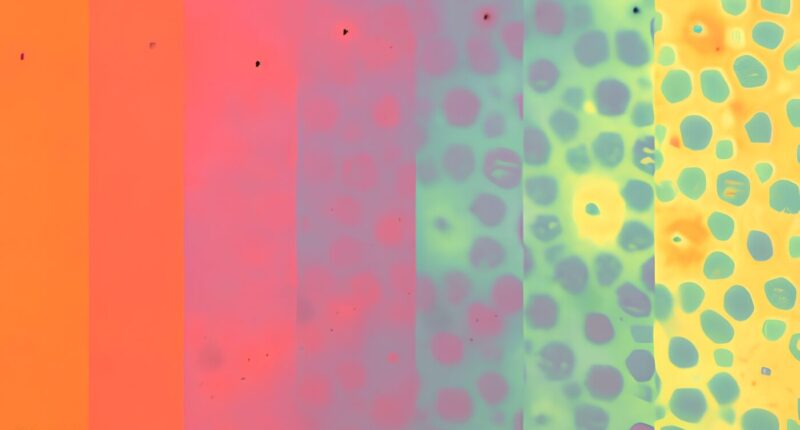

Beyond topography, the material can act as a high-fidelity display. By layering thin metallic films on the polymer to create “Fabry-Pérot resonators” — structures that isolate specific wavelengths of light — the team produced sheets that erupt into spots and splotches of vibrant colour as they swell.

The researchers also demonstrated the ability to control surface finish, shifting from glossy to matte to create a visual realism that current smartphone screens cannot match.

AI camouflage

The potential applications extend far beyond novel displays. The team is developing an autonomous camouflage system that integrates material properties with computer vision and neural networks. This would allow a device to analyse its background and instantly modulate its skin to blend in, without human input.

“There’s just no other system that can be this soft and swellable, and that you can pattern at the nanoscale,” said Nicholas Melosh, professor of materials science and engineering. “You can imagine all kinds of different applications.”

These include “smart” surfaces for robots that can alter their friction to grip or slide, biomedical devices that interact with cells via nanotexture, and next-generation encrypted communications using light.