Researchers have used sound waves to create a new form of matter that “ticks” like a clock and defies the rule that every action must have an equal and opposite reaction.

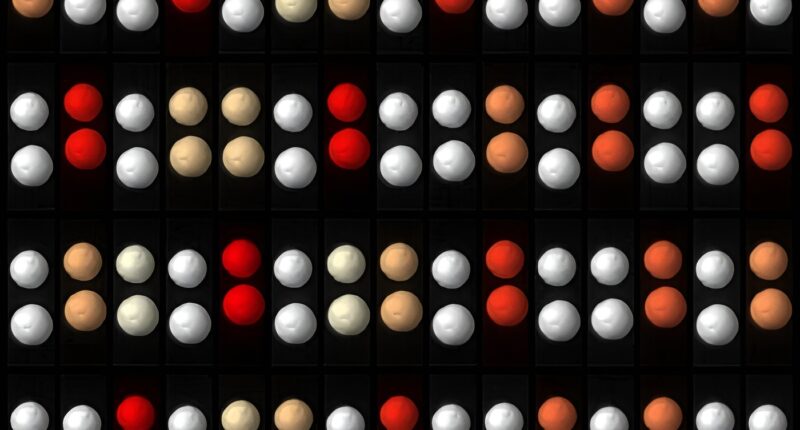

In a study published in Physical Review Letters, a team from New York University (NYU) describes a device about one foot tall that suspends particles using acoustic levitation, allowing them to be seen with the naked eye.

While time crystals — patterns of particles that repeat in time rather than space — were first theorised only a decade ago, they have typically been microscopic and complex to observe.

“Time crystals are fascinating not only because of the possibilities, but also because they seem so exotic and complicated,” says David Grier, a physics professor at NYU and the paper’s senior author. “Our system is remarkable because it’s incredibly simple.”

Defying Newton’s laws

The new crystals are formed from simple Styrofoam beads, similar to those used in packing materials. By trapping them in a “standing wave” of sound, the researchers caused the beads to levitate in mid-air.

Crucially, when these beads interact, they defy Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which states that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Instead, the particles interact “nonreciprocally” via scattered sound waves.

Because larger particles scatter more sound, they influence smaller particles far more than the smaller ones influence them, creating an unbalanced force that causes the beads to oscillate spontaneously in a repeating rhythm.

“Think of two ferries of different sizes approaching a dock,” explains Mia Morrell, a graduate student and co-author of the study. “Each one makes water waves that pushes the other one around — but to different degrees, depending on their size.”

While commercial applications are still in development, time crystals hold promise for advanced technologies like quantum computing and data storage.

The researchers also note that the “nonreciprocal” interactions observed in their mechanical device mimic certain biological processes, such as circadian rhythms and digestion, offering potential new insights into how our biological clocks function.