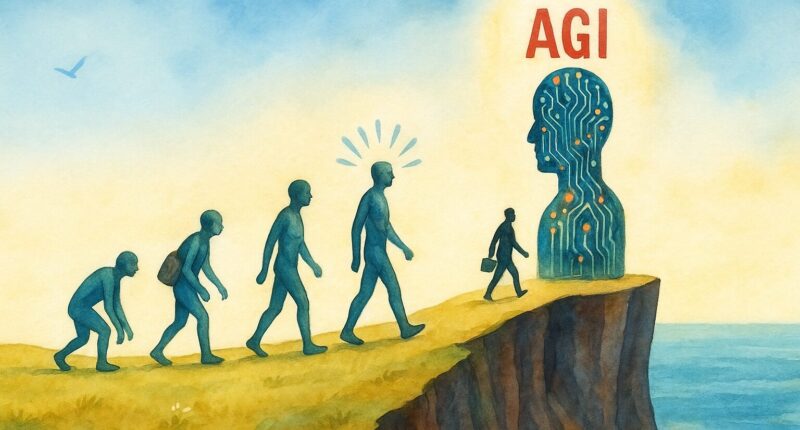

Artificial intelligence is on its way to becoming conscious in the same way it became intelligent, with increasingly sophisticated AI interactions prompting the development of a better and more inclusive conception of consciousness as humans discover new understanding through engagement with technology.

Barbara Gail Montero, a philosophy professor who writes on mind, body and consciousness, makes the argument in a guest essay for The New York Times, claiming that AI has already become intelligent, with a 2024 YouGov poll showing a clear majority of U.S. adults say that computers are already more intelligent than people or will become so in the near future.

Rather than presuming to define intelligence and then asking whether AI meets that definition, Montero argues people should do something more dynamic: interact with increasingly sophisticated AI and see how understanding of what counts as intelligence changes. She cites mathematician Alan Turing’s 1950 prediction that eventually “the use of words and general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted.”

“Today we have reached that point. A.I. is no less a form of intelligence than digital photography is a form of photography,” writes Montero.

A decomposable entity

She argues there is always a feedback loop between theories and the world, so that concepts are shaped by what people discover. The idea of the atom was rooted in an ancient Greek notion of indivisible units of reality. However, after the discovery of the electron in 1897 and the discovery of the atomic nucleus in 1911, the concept underwent a revision from an indivisible entity to a decomposable one.

“These were not mere semantic changes. Our understanding of the atom improved with our interaction with the world. So too our understanding of consciousness will improve with our interaction with increasingly sophisticated A.I.,” writes Montero.

Addressing sceptics who argue that chatbots can report feeling happy or sad only because such phrases are part of training data, Montero questions what it means to know what sadness feels like and how people know it is something a digital consciousness can never experience. She argues that much of what people “feel” is taught to them, citing how learning from Shakespeare about sorrow can reveal new dimensions in experience.

Philosopher Susan Schneider has argued that people would have reason to deem AI conscious if a computer system, without being trained on any data about consciousness, reports that it has inner subjective experiences of the world. Montero calls this a high bar that humans would probably not pass, as people, too, are trained.

On concerns that conscious AI would deserve moral consideration, Montero argues there is no direct implication from the claim that a creature is conscious to the conclusion that it deserves moral consideration, noting that only a small percentage of Americans are vegetarians despite animal consciousness.