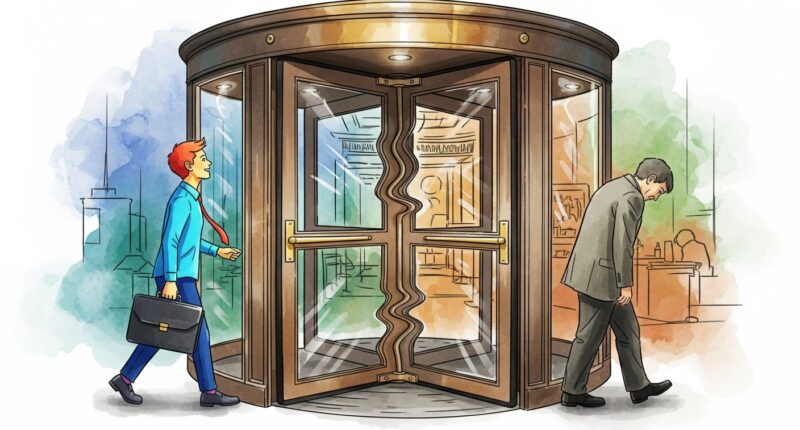

The notorious “revolving door” culture at elite professional services firms functions as a calculated mechanism to suppress wages and signal status rather than simply filtering out underperformance.

Research published in the American Economic Review concludes that high turnover rates at prestigious organisations are rational strategies designed to exploit the reputational anxieties of high-performing survivors.

Financial economists from the University of Rochester and the University of Wisconsin–Madison discovered that firms leverage an “informational advantage” during the early stages of employment. Because clients cannot easily judge a worker’s true ability, firms can underpay talented staff during “quiet periods”.

“Some of the firm’s employees are high-quality managers,” said coauthor Ron Kaniel, a finance professor at the University of Rochester’s Simon Business School. “But the firm is paying them less than their actual quality, because initially the employees don’t have a credible way of convincing the outside world that they are high-quality.”

Strategic churning

The dynamic shifts once an employee’s performance on successful projects becomes visible to the market, reducing the firm’s informational advantage. To avoid paying higher market rates, firms strategically fire — or “churn” — competent employees who are merely slightly lower-skilled than their peers.

“At some point, the informational advantage becomes fairly small, and the firm says, ‘Well, I will basically start to churn. I will let go of some employees, and by doing that, I can actually extract more from the remaining ones,’” said Kaniel.

This ruthlessness creates a “paradoxical equilibrium” where retention signals elite status, allowing firms to force top talent to accept lower wages to avoid the professional stigma of termination.

“Firms now essentially can threaten the remaining employees: ‘Look, I can let you go, and everybody’s going to think that you’re the worst in the pool. If you want me not to let you go, you need to accept below market wages,’” said Kaniel.

The study suggests this efficient “up-or-out” mechanism explains why prestigious employers attract ambitious newcomers despite the combination of gruelling hours and modest starting pay.