A team of engineers has developed a new generation of “smart” microrobots made from simple gas bubbles that can navigate through the body and hunt down tumours on their own.

In a study published in Nature Nanotechnology, researchers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the University of Southern California (USC) revealed that these “bubble bots” successfully treated bladder tumours in mice, reducing tumour weight by roughly 60 per cent compared to standard drug treatments.

While the potential for microrobots in medicine has long been theorised — ranging from performing non-invasive surgery to delivering drugs — creating devices that are biocompatible, effective, and cheap to manufacture has remained a significant hurdle. This new development marks a departure from complex fabrication methods, simplifying the robot down to a microscopic bubble equipped with a chemical “engine”.

“We thought, what if we make this even simpler, and just make the bubble itself a robot?” says Wei Gao, a professor of medical engineering at Caltech who led the study. “We can make bubbles easily and already know they are very biocompatible. And if you want to burst them, you can do so immediately.”

Powered by ‘biofuel’

Previous iterations of microrobots developed by Gao’s team were fabricated in cleanrooms using 3D-printed hydrogel shells. While effective, they required specialised equipment to produce.

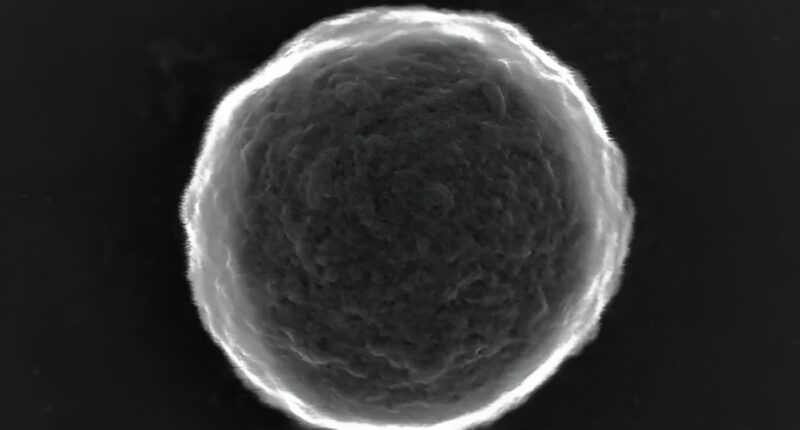

To create the new bubble bots, the team simply used an ultrasound probe to agitate a solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA), a standard animal protein. This process generates thousands of microbubbles with protein shells almost instantly.

To turn these passive bubbles into active robots, the scientists utilised the amine groups found on the protein shells — chemical structures that allow for easy modification. By attaching the enzyme urease to the surface, they created a propulsion system that runs on the body’s own waste.

Urease catalyses the hydrolysis of urea, a waste product abundant in the body, producing ammonia and carbon dioxide. Because the enzyme is not distributed evenly across the bubble’s surface, the chemical reaction pushes the bubble forward, effectively acting as a biofuel engine.

Homing in on cancer

The team developed two distinct methods for guiding these bubbles to their targets.

The first method involves “remote control”. By attaching magnetic nanoparticles to the shell, the researchers could steer the bubbles through the body using external magnets and track their progress via ultrasound imaging.

However, the second version of the bot is capable of autonomous navigation. The researchers took advantage of the fact that tumours and inflamed tissues produce high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide compared to healthy cells. By attaching a second enzyme, catalase, to the bubble, the robot becomes chemically attracted to the tumour.

Catalase reacts with hydrogen peroxide to create water and oxygen. Through a process known as chemotaxis, the bubble automatically moves up the hydrogen peroxide concentration gradient toward higher concentrations, effectively steering itself directly to the cancer site.

“In this case, you don’t need any imaging; you don’t need any external control. The robot is smart enough to find the tumour,” Gao explains. “The bubble robot’s autonomous motion, together with its ability to sense the hydrogen peroxide gradient leads to this targeting.”

Explosive delivery

Once the robots reach the tumor, they do not simply release the drug passively. The researchers apply a focused beam of ultrasound to burst the bubbles.

This “on-demand trigger” creates a forceful popping action that drives the therapeutic cargo — in this case, the anti-cancer drug doxorubicin — deep into the tumour tissue. This penetration is significantly more effective than the slowly degrading hydrogel robots previously used by the team.

The efficacy of the system was demonstrated in mouse models, where the bubble bots achieved a major reduction in tumour size over a three-week period.

“This bubble robot platform is simple, but it integrates what you need for therapy: biocompatibility, controllable motion, imaging guidance, and an on-demand trigger that helps the drug penetrate deeper into the tumour,” says Songsong Tang, the paper’s lead author and a former postdoctoral scholar at Caltech. “Our goal has always been to move microrobots closer to real clinical use, and this robotic design is a big step in that direction.”