Engineers have developed a novel design for a solar-powered data centre that would orbit the Earth, potentially offering a scalable solution to the massive energy and water consumption associated with artificial intelligence.

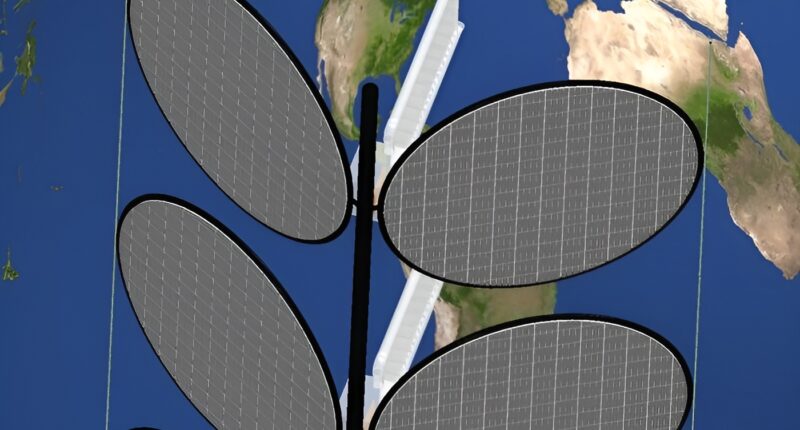

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn Engineering) propose a structure reminiscent of a “leafy plant,” utilising fibre-like tethers to hold computing hardware and solar panels in place. The design, presented at the 2026 American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) SciTech Forum, relies on natural orbital forces rather than motors to maintain its orientation, making it uniquely scalable.

The proposal addresses a growing environmental crisis: as AI models become more complex, terrestrial data centres are straining electricity grids and consuming vast quantities of water for cooling.

“This is the first design that prioritises passive orientation at this scale,” says Igor Bargatin, Associate Professor in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics at Penn and senior author of the study. “Because the design relies on tethers — an existing, well-studied technology — we can realistically think about scaling orbital data centres to the size needed to meaningfully reduce the energy and water demands of data centres on Earth.”

The physics of tethers

While startups and governments have previously floated the idea of space-based computing, most existing proposals face significant logistical hurdles. Constellations of individual satellites require millions of units to make a difference, while massive rigid structures are too complex to assemble in space with current technology.

The Penn team’s design occupies a “middle ground.” It utilises tethers — long, flexible cables that have been studied in space exploration for decades.

When placed in orbit, these tethers are pulled taut by two competing forces: Earth’s gravity pulling downward and the centrifugal force of orbital motion pulling upward. This natural tension keeps the structure vertically aligned without the need for fuel-heavy thrusters or complex guidance systems.

In the proposed design, thousands of computing nodes — containing chips, cooling hardware, and solar panels — would be strung along these tethers like beads on a necklace.

Solar pressure steers

A key innovation of the design is its ability to stay pointed at the sun using “solar pressure.” The researchers found that using thin-film materials and slightly angling the panels allows the gentle physical pressure exerted by sunlight to act like wind on a weather vane.

“We’re using sunlight not just as a power source, but as part of the control system,” says Bargatin.

This allows the system to remain passive. Unlike traditional satellites that require constant active adjustments, this structure aligns itself using the laws of physics, significantly reducing weight and mechanical complexity.

A belt of AI around the planet

The study suggests that a single tethered system could stretch for tens of kilometres, supporting up to 20 megawatts of computing power — roughly equivalent to a medium-sized terrestrial data centre.

The researchers emphasise that the system is designed specifically for AI “inference”—the process of querying a tool like ChatGPT after it has already been trained—rather than the training process itself. While the latency of sending data to orbit might preclude training, the explosive growth in user queries makes inference a prime candidate for off-worlding.

“Imagine a belt of these systems encircling the planet,” says Bargatin. “Instead of one massive data centre, you’d have many modular ones working together, powered continuously by sunlight.”

Resilience to space debris

Any structure in orbit faces the threat of micrometeoroids — tiny, high-speed debris. To test the design’s durability, the team ran simulations of cumulative impacts over time.

“It’s not a matter of preventing impacts,” says Jordan Raney, Associate Professor in MEAM and co-author. “The real question is how the system responds when they happen.”

The simulations revealed that the tethered structure behaves like a wind chime. When struck, the impact causes a wobble that travels along the tether and naturally dissipates. Furthermore, because each computing node is supported by multiple tethers, the system acts as a redundant mesh; even if one line is severed, the data centre continues to function.

The team is now working to refine the cooling systems — which must radiate heat into the vacuum of space — and plans to build a small-scale prototype.

“Much of the growth in AI isn’t coming from training new models, but from running them over and over again,” says Bargatin. “If we can support that inference in space, it opens up a new path for scaling AI with less impact on Earth.”