Unprecedented images of exploding stars have revealed that these cosmic blasts are far more complex than previously understood, overturning the long-held view that nova eruptions are simple, single events.

An international research team has successfully captured detailed images of two stellar explosions — known as novae — within days of their eruption, providing the first direct evidence of multiple outflows and significant delays in the ejection of material.

The study, published in Nature Astronomy, utilised a cutting-edge technique called interferometry at the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) Array in California. This approach allowed scientists to combine light from multiple telescopes to achieve the sharp resolution necessary to watch the explosions evolve in real time.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy — they are laboratories for extreme physics,” said Laura Chomiuk, physics and astronomy professor at Michigan State University. “By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material, and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.”

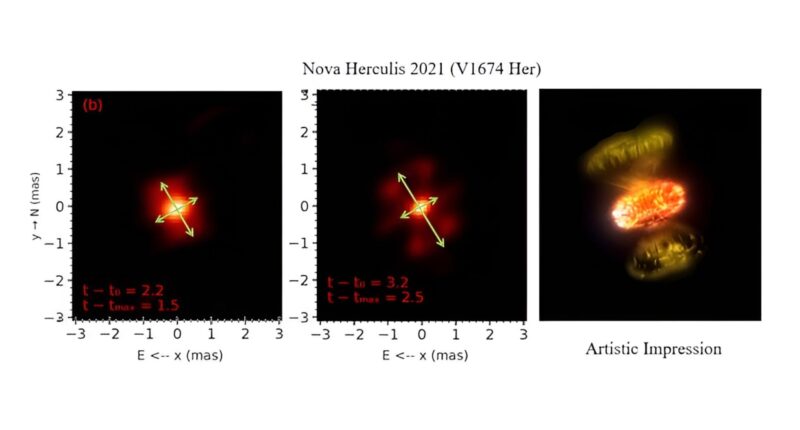

The researchers imaged two distinct novae that erupted in 2021, discovering that each behaved differently from theoretical expectations.

Fastest eruptions

Nova V1674 Herculis, one of the fastest eruptions on record, revealed two distinct, perpendicular outflows of gas. This provided evidence that the explosion was powered by multiple interacting ejections rather than a single impulsive blast. Crucially, these flows appeared simultaneously with high-energy gamma ray detections from NASA’s Fermi telescope, directly linking the colliding outflows to shock-powered emissions.

In contrast, Nova V1405 Cassiopeiae evolved much more slowly. The star surprisingly held onto its outer layers for more than 50 days before finally ejecting them, providing the first clear evidence of a delayed expulsion.

The findings challenge the traditional understanding of novae, which occur when a white dwarf star undergoes a runaway nuclear reaction after stealing material from a companion star. Previously, astronomers could only infer the early stages of these eruptions indirectly.

“These observations allow us to watch a stellar explosion in real time, something that is very complicated and has long been thought to be extremely challenging,” said Elias Aydi, lead author and professor of physics and astronomy at Texas Tech University. “Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold. It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video.”