Physicists are building a machine to solve the biggest problem in science by detecting the elusive particles that make up gravity.

A collaboration between Stevens Institute of Technology and Yale University has begun work on the world’s first experiment explicitly designed to detect individual “gravitons” – the hypothetical quantum particles of gravity.

Supported by the W. M. Keck Foundation, the project aims to achieve what was long considered physically impossible: bridging the gap between quantum theory and Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Modern physics is currently divided into two incompatible frameworks. Quantum theory explains the universe in terms of discrete particles, while general relativity describes gravity as a smooth curvature of space and time. To unify them into a “theory of everything,” gravity must be made of particles, but detecting a single graviton has historically been dismissed as a hopeless task.

“For a long time, graviton detection was considered so hopeless that it was not treated as an experimental problem at all,” said Igor Pikovski, assistant professor at Stevens.

“What we found is that this conclusion no longer holds in the era of modern quantum technology.”

Waves and quantum

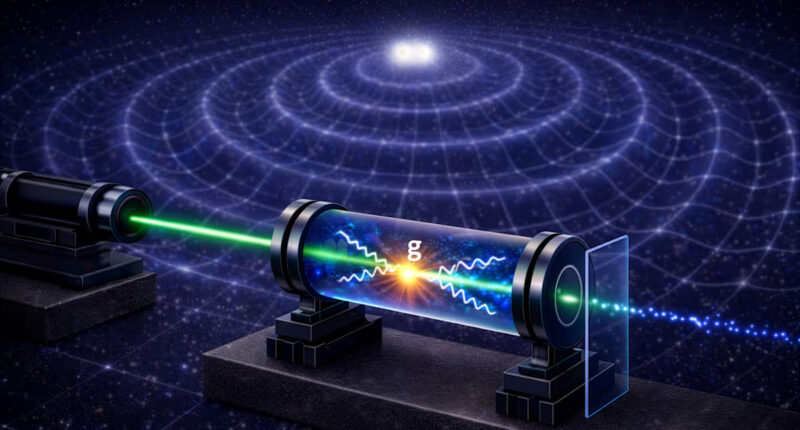

The new experiment is based on a breakthrough discovery published by Pikovski’s team in 2024, which argued that graviton detection is possible by combining two recent scientific advances: gravitational wave detection and quantum engineering.

Gravitational waves – ripples in space-time caused by massive cosmic events like black hole collisions – are now detected routinely. If gravity is quantum, these waves are actually vast collections of gravitons.

Pikovski realised that a passing gravitational wave could, in principle, transfer exactly one quantum of energy – a single graviton – into a sufficiently massive quantum system. While gravitons rarely interact with matter, a system at the “kilogram scale” exposed to intense waves could enable absorption.

The machine

To build the detector, Pikovski has teamed up with Jack Harris, a professor at Yale University.

The team is developing a “superfluid-helium resonator” roughly the size of a centimetre. This gram-scale cylinder will be immersed in superfluid helium and cooled to its quantum ground state.

Using laser-based measurements, the researchers plan to detect individual “phonons” – the vibrational units that gravitons are converted into when they hit the detector.

“We already have the essential tools,” said Harris. “We can detect single quanta in macroscopic quantum systems. Now it’s a matter of scaling.”

The current experiment is designed to establish a blueprint. By demonstrating that this platform works at the gram scale, the team hopes to pave the way for the next iteration, which will be scaled up to the sensitivity required for direct graviton detection.

“Quantum physics began with experiments on light and matter,” Pikovski said. “Our goal now is to bring gravity into this experimental domain, and to study gravitons the way physicists first studied photons over a century ago.”