Treating mental illness effectively requires the brain to abandon well-worn hiking trails for new routes, according to a theoretical framework that suggests psychotherapy works by physically altering internal navigation systems.

A paper published in Perspectives on Psychological Science proposes that the breakthrough moments in therapy occur when the brain expands its “cognitive map” to reveal alternative destinations, utilising the same neural hardware used to navigate physical space.

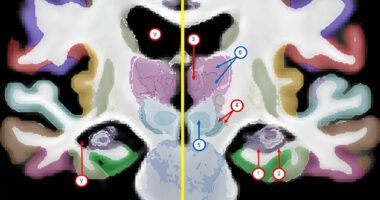

Jaan Aru, associate professor at the University of Tartu, and Nick Kabrel, a graduate student at the University of Zurich, argue that the brain organises abstract concepts using the same grid cells and place cells in the hippocampus that it uses to coordinate movement in the three-dimensional world.

“The brain is highly likely to make use of this mapping system in these other domains, too,” said Aru. “This idea of mental navigation could be a very general framework to understand thinking and abstract cognition.”

The overgrown trail

The framework relies on a distinct metaphor: the researchers compare a depressive thought pattern to a hiking trail in a forest. The more a specific path is used, the wider and more accessible it becomes, making it the brain’s automatic choice for future journeys.

A depressed patient might view every social interaction through a “negative lens,” reinforcing this specific neural pathway until it becomes the only visible route. Therapy functions by forcing the traveller to stop, check the map, and hack a new path through the undergrowth.

“When I search through memory or search in my mind, it always feels as if I am navigating in some kind of environment,” said Kabrel.

Kabrel suggests therapists can explicitly use this framing to help patients break cycles, telling them: “This is the place where we are stuck. We come back here every time, but we need to expand this.”

Mapping the mind

The researchers argue that this “narrow map” problem extends beyond diagnosed mental illness to the general population, limiting how society functions by trapping people in rigid loops of thought.

“Often the problem is that people have very narrow maps, very narrow ways of thinking. And it’s a very general problem,” said Aru. “Our goal as a society could be to expand the way people actually think.”

The team is calling on neuroscientists to design experiments testing whether successful therapy sessions correlate with activity in the brain’s grid cells, potentially bridging the gap between cognitive psychology and hard neuroscience.