Roboticists have successfully transformed dinner leftovers into high-torque machines, using discarded langoustine shells to build functional grippers that outperform artificial materials in strength and flexibility.

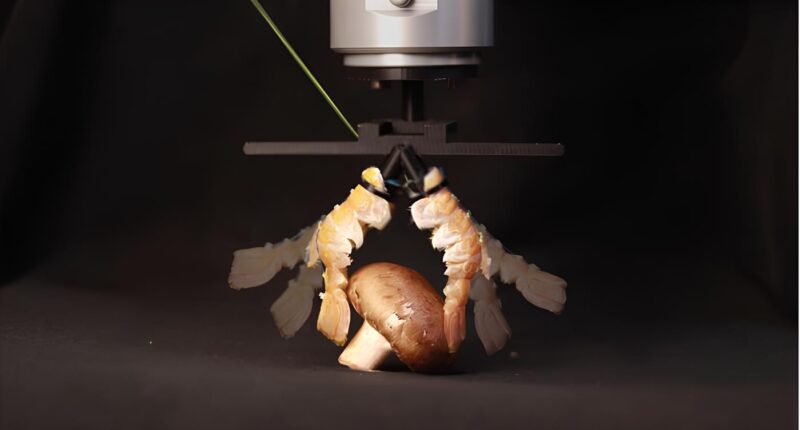

Researchers from the Computational Robot Design and Fabrication Lab (CREATE Lab) at EPFL combined the biological exoskeletons with synthetic components to build manipulators capable of handling objects weighing up to 500 grams. The system embeds an elastomer inside the shell to control movement, whilst a silicon coating reinforces the structure.

“Exoskeletons combine mineralised shells with joint membranes, providing a balance of rigidity and flexibility that allows their segments to move independently,” says Josie Hughes, head of the CREATE Lab. “These features enable crustaceans’ rapid, high-torque movements in water, but they can also be very useful for robotics.”

The study, published in Advanced Science, demonstrates three specific applications: a manipulator, grippers that can grasp objects ranging from a highlighter pen to a tomato, and a swimming robot that moves at 11 centimetres per second.

Beyond functionality, the project aims to address sustainability in robotics by replacing metal and plastic with biodegradable waste.

“To our knowledge, we are the first to propose a proof of concept to integrate food waste into a robotic system that combines sustainable design with reuse and recycling,” says Sareum Kim, researcher at CREATE Lab.

The team acknowledges that natural variations in biological structures present challenges, as unique shell shapes cause grippers to bend differently. Future iterations will require advanced controllers to manage these inconsistencies.

“Although nature does not necessarily provide the optimal form, it still outperforms many artificial systems and offers valuable insights for designing functional machines based on elegant principles,” adds Hughes.